The Annaka Radio Story

by Bob Rydzewski, CHRS Deputy Archivist

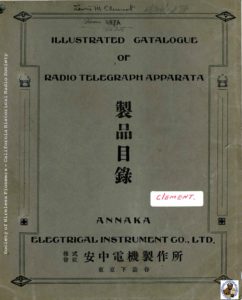

Long before there was Sony, a company in Tokyo was designing and manufacturing high-quality radio and electronics equipment. Nearly forgotten today, we were reminded of the existence of Annaka Denki Seisakujo, Ltd. thanks to Society of Wireless Pioneers member Lewis Clement, 153-SGP, whose copy of their 1920 illustrated catalog was recently discovered in the SoWP archives.

Clement was a true pioneer, had been a shipboard radio operator, established and/or worked at Avalon station “A” and KIE (Kahuku, Hawaii) and would go on to become a Vice President at RCA. It isn’t clear how the Annaka catalog came into his (and later SoWP’s) possession, since by 1920 he was no longer sailing the seven seas, at least as a crew member. But another “Sparks” of that era (when they really did use sparks), E.J. Quinby, 402-SGP, had sailed to Japan back in December 1919, and left us a description of a Tokyo company that may or may not have been Annaka. In his book about his career on a tramp steamer, Ida Was a Tramp (Exposition Press, Hicksville, NY, 1975), Quinby tells of visiting the factory of a “Tokyo Radio Company, Ltd.” thanks to Suji Yamamoto, an acquaintance he made on the train to Tokyo who was a radio operator on the Yufuku Maru and a friend of the factory manager. We have not yet been able to trace any company by that name although several others, including the forerunner of Japan Radio Company, Ltd. did exist.

“We passed down a long path between rows of thatched-roof bamboo stalls in each of which attractive young native girls… turned out tiny components with graceful, dainty fingers.” He describes a visit to the glassblowing section where which the women created the glass envelopes for vacuum tubes, a section where the tube elements were set into the bases and welded into place, and a stall where the tubes were exhausted either with a single-stage vacuum pump for “soft” detector tubes or a two-stage (probably mercury diffusion) pump for a “hard” vacuum. Quinby bought a few tubes for one yen each and later wished he’d bought whole cases full of them. Considering how well they worked and how much more expensive the equivalent American tubes were back in San Francisco, he could have made “a tidy profit” selling them there.

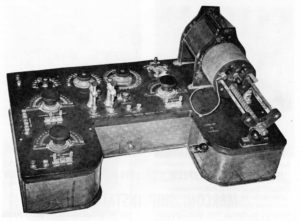

1920 Annaka Catalog, page 49

A number of Japanese companies were manufacturing electrical equipment at the time, so we can’t be sure that the one Quinby visited was Annaka, but that in itself points out just how active the Japanese radio business was at that early date. Quinby himself mentions his experience with Japanese purchases of electric railroad cars, which he had previously been involved with. “They had ordered two multiple-unit passenger cars of the latest type… When I had voiced the opinion that this was probably the forerunner of a larger order, my immediate superior had disillusioned me by explain that it was the Japanese custom to order just two, one of which they would keep intact as a sample, and the other would be carefully taken apart, piece by piece, so that the parts could serve as patterns for their own production.” According to Gerald Tyne, in his Saga of the Vacuum Tube (Prompt Publications, Berkeley Heights, NJ, 1977), Walter Schare, who had been a salesman for Deforest, spoke of a standing order he had with the Mitsui Company for “two pieces of everything de Forest sold” again suspecting that one was preserved and the other reverse engineered. Now, it could have all been just a myth based on Americans’ ideas of their own superiority and irreplaceability, but considering the similarities in some of the Japanese and American versions and the fact that reverse engineering could be (and still may be) seen as an economical way to “catch up” on technology provided lawsuits don’t interfere, it seems quite possible.

Little information on Annaka exists, at least in the West. According to the radiomuseum.org, the company was founded in 1900 primarily for the Japanese military communications market. They started out in wireless with a bang: their first transmitter was used to set off fireworks at the 1903 Japan Industry Promotion Exposition. Almost since their beginning, Annaka had equipped Japanese Naval vessels. In 1905 their Type 36 set played a role in the Battle of Tsushima Strait in which the Russian fleet was effectively annihilated, leading to Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. Annaka became an important player in Japanese communications, with radiotelephone service between Toba, Toshijima, and Kamijima via its TYK wireless system (patented by Torikata, Yokoyama, and Kitamura) as early as 1916. By 1920 they could boast that “more than 80% of Wireless Stations in actual service on board vessels sailing under the Japanese flag are supplied by ourselves.

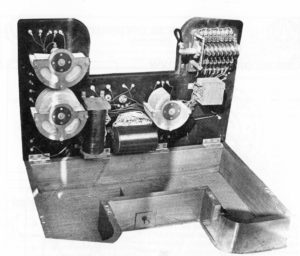

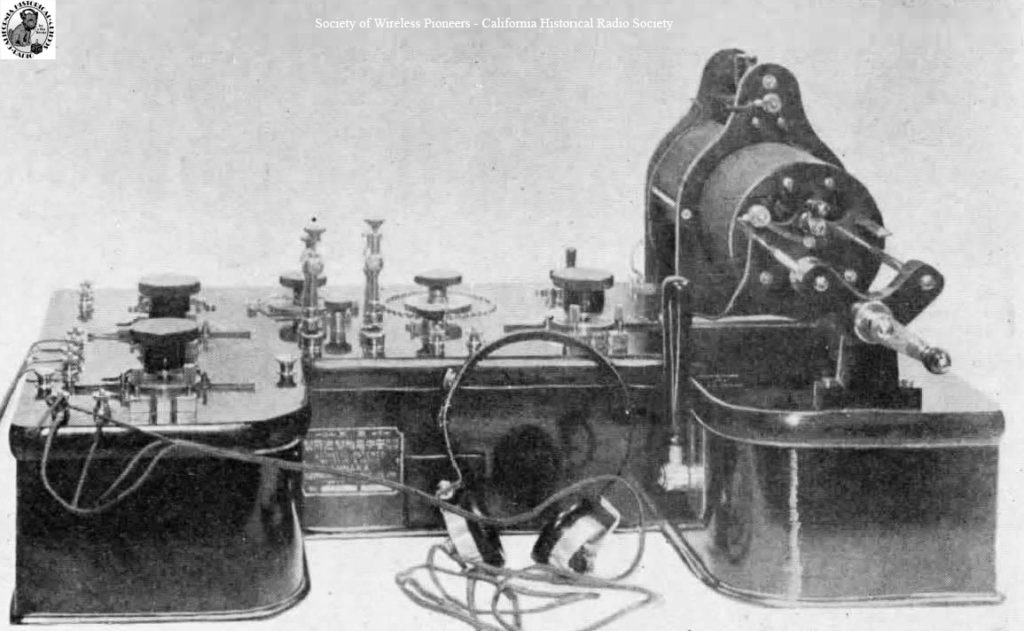

Annaka TYK radiotelephone. From 1920 Annaka catalog, p. 56.

According to the book History of Electron Tube by Sogo Okamura (IOS Press, Washington, DC, 1994), the motivation for Annaka’s 1920’s radio manufacturing was “trying to avoid overseas products invade [sic] Japan too much”. The 1920 Annaka catalog lists a wide variety of industrial quality engines, motor generators, high voltage equipment, transmitters, receivers, and wireless accessories. Of particular interest is their line of receivers, several of which have a distinctive look to them. Few of these sets are known to exist anymore. However, a couple turned up in the San Francisco Bay area and are the subject of an article by the late, great antique radio collector and dealer Paul Giganti.

Annaka receiver from p. 20, 1920 catalog.