Three Wireless Pioneers Walk into a Bar:

Stories from San Francisco’s Storied Waterfront

By Bob Rydzewski

Deputy Archivist and History Fellow, CHRS

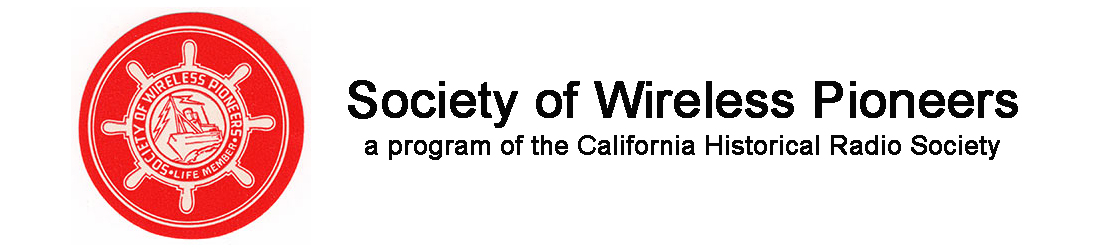

The place: Charlie’s Bar on Drumm Street in San Francisco, along which the Scandinavian Sailor’s House, the New Harbor Hotel and the Maritime Hall Building could also once be found. The date: sometime in 1955. The occasion: three old-time wireless (radio) operators meet to quench their thirst and reminisce. Between them they have more than a century-and-a-half of wireless experience and participated in the making of history. Let’s look at them individually.

Jack Irwin

At far left is legendary old-timer Jack Irwin. Born in Victoria, Australia in 1884, Jack started out as a landline (wired) telegrapher. He enlisted during the 2nd Boer War and served as telegrapher in Natal during the Zulu rebellion, which is “going back a bit” as they say! He was employed by the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company—later renamed Marconi—which sent him overseas early in the new century, possibly on the same ship as Guglielmo Marconi, to help establish Marconi’s American operation. Among the things he is said to have accomplished there was the recommendation for hiring and/or the training of a promising young man by the name of David Sarnoff, who would eventually succeed in becoming the President of RCA!

In those early days, though, Irwin was more famous for being the wireless operator at Marconi’s Siasconset, Massachusetts station who first picked up the CQD (pre-SOS distress call) from Jack Binns on the RMS Republic, which had been rammed by another ship, the Florida, on the night of January 23, 1909 and was sinking. Irwin handled the emergency traffic for the next 3 days and ultimately all but 6 of 1656 lives were saved. This first use of wireless telegraphy to prevent a major loss of life at sea monopolized newspaper front pages everywhere and inspired thousands of young men to want to become wireless operators. [1] Binns, much to his own consternation, became an overnight celebrity and remained in the public eye for years. The impact of the Republic CQD rescue would only be surpassed by that of the Titanic disaster 3 years later.

But that wasn’t the end of Irwin’s adventures. The following year found him in circumstances that were “certainly the strangest an operator ever found himself in” as wireless operator aboard the airship America. [2] This was a dirigible, essentially a giant balloon filled with more than 300,000 cubic feet of highly flammable, odorless hydrogen gas. Below the balloon was suspended a gondola, and below that a lifeboat equipped with a wireless set that transmitted by spark! It took no small amount of courage just to tap that key for the first time. Newspaperman and news maker Walter Wellman was determined to be the first to cross the Atlantic by air. [3] Critics scoffed at the idea, calling the America a “worn-out gas bag” with “an old coffee-mill for motor”. [4] The crew vowed to make them eat their words. On October 15, 1910 manned by a crew of 6 and over the protests of an onboard cat named Kiddo (“This cat is raising hell. I believe it’s going mad,” said Irwin), the America departed from Atlantic City, bound for the UK. [5,6]

Marconiman Irwin had at his disposal the latest in technology: a Marconi spark transmitter and receiver equipped with a magnetic detector (“Maggie”). The noise of the motor, however, made it difficult to hear anything through the headphones. After several days and at about 1000 miles out, an emergency occurred. Motor problems forced the shutdown of the main motor. Worse still, the cold fog was freezing onto the surface of the airship, weighing it down while the low temperatures contracted the gas, making the balloon less buoyant. An Atlantic gale took control of the America which had trouble staying airborne. Irwin sent out his CQD, the first ever sent from an aircraft, hoping someone would hear it, and the crew and its mascot took to the lifeboat, still suspended above the sea. They spotted the welcome sight of the lights of a ship in the distance, and Irwin repeatedly tried to call it, but to no avail. As they got closer, in what could have been designed for a battery advertisement, Irwin took out a flashlight and started flashing Morse signals to the ship, repeating over and over that they needed help and they were equipped with wireless. The signals were spotted by the crew of the RMS Trent, who awoke their off-duty, slumbering radioman (24-hour radio coverage not yet being required), and communications were soon established. In a tricky and very first air-sea (or sea-air) rescue, the Trent was able to pick up all aboard, including Kiddo, now renamed Trent. Even after failing to cross the Atlantic, the crew had set records and was treated to a tickertape parade upon their arrival in New York. Once again Irwin had become a celebrity radio-telegrapher. For a while he toured the lecture circuit of Vaudeville houses relating his experiences to rapt crowds, an opportunity he had correctly foreseen while the airship was in peril.

Never one to rest on his laurels, Irwin would volunteer in World War I, becoming a Lieutenant in the US Army Air Service, continue his Marconi (and later RCA) career as Station Manager at their Seattle Station, act as Assistant Radio Officer (under Chief Elmo Pickerill) aboard the SS Leviathan, write occasional articles for newspapers, and eventually enjoy retirement in his Hayward, California home. Although a member of the Veteran Wireless Operators Association (VWOA), he died in 1958, a decade before the Society of Wireless Pioneers was founded.

Howard Cookson

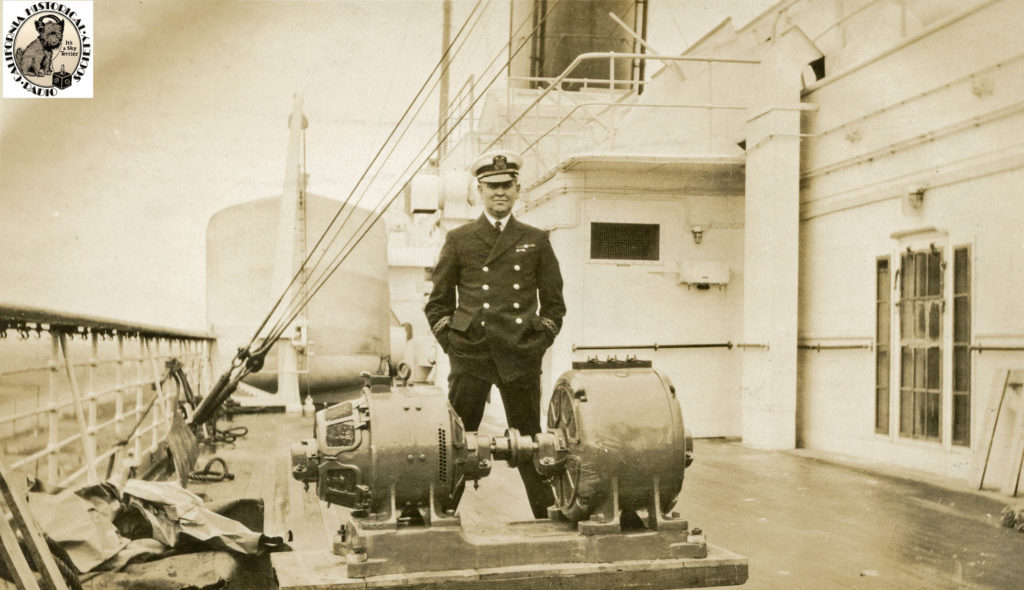

To Irwin’s left in the first photo stands Howard Cookson, 140-SSGP, also shown to the far right in the photo below. He was born in San Francisco on November 20, 1894. Back in the days of the Bay Counties Wireless Club (1907-1914) Cookson, callsign SHC, in Palo Alto, was a member. Other members of this early and elite club included Haraden Pratt (San Francisco) who would eventually become an adviser to US Presidents, Ray Newby (San Jose) who worked with early broadcaster “Doc” Herrold, and Lewis Clement (Oakland). [7-9] One of the club’s early achievements was wireless reporting of “The Big Game” between Stanford and UC Berkeley football teams in 1908 (spoiler alert: Stanford won 12-3). [10] Like many early hams, Cookson became a ship Radio Officer, and had a long and distinguished career. He held a Certificate of Skill (CoS), the earliest type of commercial wireless license.

Cookson related one of his adventures aboard a sailing ship in the Society’s Sparks Journal. [11] By way of background, he notes that Alaska canneries were so in need of seasonal workers that they’d worked out a deal with the San Francisco police. Every spring, “the police judges used to line up the bums, drunks, and derelicts before them and say, ‘Okay boys. Six months in the county jail, or ship to Alaska. What’ll it be?’”. Since the latter was only a 3-month (if more chilling) sentence and they could earn a little money, most chose to head north. Cookson, who had been assigned as radio operator at KMG in remote Nushagak, Alaska, boarded the wooden hulled, square-rigged, 3-masted barkentine Standard along with about 200 of these fine cannery recruits in the spring of 1917. Despite early wireless laws, the ship carried no radio except for a small tube receiver that Cookson brought with him. The Standard took more than a month to get near its destination in Alaska. In the middle of the night the ship piled up on the rocks at Cape Constantine and started taking on water; the Captain had been off by 40 miles in his position calculations. What to do?

Again, in a tale that could have been torn from the pages of a vintage boy’s magazine, Cookson had spotted an old spark coil onboard. He quickly rigged up a junk transmitter with a 1/8” spark gap connected to a wire run up one of the masts. “I didn’t know if it would work, but by that time I would have tried anything, even a Ouiji Board,” he noted. As the ship pounded against the rocks, Cookson started sending SOS calls on a makeshift key. On the third try his call was acknowledged by the Kvitchak Station. “I know now how people feel when they win the Irish Sweepstakes,” he said. The Standard soon went under, but not before everyone had taken to the lifeboats. Given one sardine, some crackers, and a swig of whiskey per passenger per day in the rocking boats, four long days and nights later they were picked up by tugboats. The experience left the veteran radioman with a distaste for sardines and whiskey ever after, which may explain why he’s probably drinking beer in the photo.

Cookson was a Director of the Society of Wireless Pioneers and became a silent key on May 22, 1975.

Leslie F. Byrne

The third person from left in the top photo is Les Byrne, 227-SGP. We know much less about him than the other two wirelessmen, but perhaps will discover more as we comb through the SoWP archives. Byrne was an old-timer who worked with A.Y. Tuel at the San Francisco “Beach Station” back in 1907. Unfortunately, bad luck seems to have followed him, at least in his later years. He and his wife suffered from poor health for many of their senior years, and his misfortune culminated when he was struck by a train and killed in Mountain View, California on February 27, 1974.

As for Charlie the Barkeep we know nothing other than that he apparently ran his own establishment and must have heard these and many other incredible tales in his time.

Sources of information for this article include both Society of Wireless Pioneer archival materials and others, including John Dilks, 5729-TA, to whom we are especially indebted. We also thank CHRS Archivist Bart Lee and CHRS Board Chair Mike Adams for reviewing this article and sharing their wealth of knowledge on early radio history.

[1] Karl Barslaag, SOS to the Rescue (New York, Oxford University Press, 1935), pp. 18-39.

[2] Jack Irwin, “Experiences of the First Marconi Airship Officer”, The Marconigraph, November 1911, p. 4.

[3] The most accurate and well-written account of the airship’s voyage can be found in a series of articles by SoWP member John Dilks (K2TQN) in his Vintage Radio columns that appeared in QST between August 2010 and January 2011. We are indebted to Mr. Dilks for much of the information on the Airship America presented here.

[4] Quoted in Laura Trevelyan, “Airship America’s landmark crossing attempt recalled”, BBC News, October 15, 2010, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-11547569. Checked January 2, 2019.

[5] Quoted in Walter Wellman, The Aerial Age: A Thousand Miles by Airship Over the Atlantic Ocean,” (New York, Keller & Co., 1911), p. 339. Available at https://archive.org/details/aerialage00wellgoog/page/n8. Checked January 2, 2019.

[6] For more on Kiddo the cat, see https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/kiddo-cat-reluctant-aviator. Checked January 3, 2019.

[7] For more about Herrold, see http://www.charlesherrold.org/read.html. Checked January 4, 2019. Also, see Greb G, Adams M. Charles Herrold, Inventor of Radio Broadcasting (McFarlnd & Co., Jefferson, NC, 2003).

[8] For more about Clement, see http://centpacrr.com/LMClement/index.html. Checked January 4, 2019.

[9] Lewis M. Clement, “Operating Experiences of a Pioneer,” Sparks Journal, Vol. 7, No. 4, June 21, 1985, p. 7. Available at http://www.silentkeyhq.com/wireless_archive/SOWP/Vol7No4.pdf. Checked January 2, 2019.

[10] For more about the Bay Counties Wireless Club, see Bart Lee, “Wireless Comes of Age on the West Coast,” AWA Review, Vol. 24, 2011, pp. 12-13.

[11] Howard Cookson, “How ‘The Standard’ Went Down,” Sparks Journal, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1980, p. 16. Available at http://www.silentkeyhq.com/wireless_archive/SOWP/Vol3No4.pdf. Checked January 2, 2019.