THE JOE HALLOCK STORY

From Society of Wireless Pioneers

Jack Binns’ Chapter Historical Record

Compiled by Dr. Erskine H. Burton, Historian, transcribed and copyedited by CHRS Deputy Archivist Bob Rydzewski, with edits and footnotes by CHRS Archivist Bart Lee

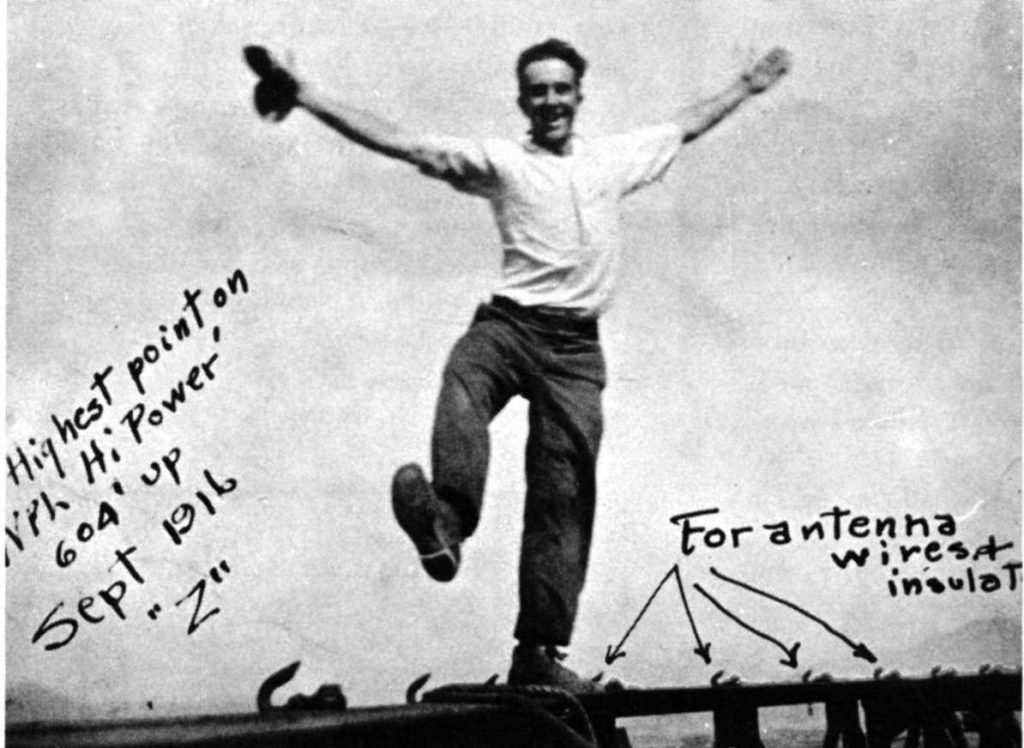

Joseph H. Hallock, 148-SGP Atop NPL (San Diego) Antenna

Joe was initiated in 1908 into what developed as a distinguished radio career spanning over half a century, taking him to many parts of the world, and involving some big construction jobs.

Joe built his first “ham” station from the ground up, starting with a 2 kW transformer which he painstakingly assembled from pressed iron can cut with tin snips; many thousands of turns of wire wound with the aid of a foot pedal sewing machine as the wire was run through melted wax, the whole assembly finally being encased in oil. “This, I believe, was the crowning achievement of my life,” says Joe. Thus, with 2 kW of power to crash the open straight gap, a carborundum detector and a flat-top antenna, station “FU” in Portland went on the air with “a mighty blinkin’ of the lights.” Joe established “reasonably dependable” communication with other Portland stations, two of which were operated by Charlie Austin (‘SN’) and Cliff Watson (‘RPT’, later SOWP member 403-SGP).

In 1910 the United Wireless Co. had two commercial stations in Portland–‘DZ’ in the Perkins Hotel, and ‘PE’ in Council Crest. Through the acquaintance of United’s local manager, C.B. Cooper, Joe and Cliff “broke in” in commercial wireless here. They both had started college in Corvallis in September 1909, moving Joe’s station to his fraternity’s second bathroom and operating it with the call ‘CZ’. Operating from these quarters obviously often was disrupted, so following some mild complaints the gear was moved to more spacious quarters in the Mechanical Hall.

During the summer of 1910 Joe got his first commercial operating job with Continental Wireless Company’s downtown Portland station ‘O2′. The station had a 5 kW, 240 cycle rotary gap transmitter with a “beautiful note.” However, unhappily, Continental Wireless soon went bankrupt, owing Joe three months’ salary. Joe thought Lee de Forest was among those interested in this short-lived concern.

In the spring of 1911, Joe and his pal Cliff Watson headed for San Francisco and the United Wireless office there. Through the SF manager for United, Mr. L. (“Larry”) Malarin, they both landed sea-going operators’ jobs. Joe shipped out on the ‘J.B. Stetson,’ a steam schooner. Shortly thereafter he transferred to a larger ship, the ‘Norwood.’ United had ordered that operators could no longer accept “franked” messages from ships’ captains; so when Joe refused to accept such a message from The Norwood’s captain, the skipper called it “mutiny” and promptly cut off power to the radio room. On the ship’s arrival in S.F. the captain insisted that Joe be fired, whereupon he was transferred to a better ship, the ‘W.S. Porter,’ at a raise of $10.00 per month! No action was taken against the captain, who today would have been charged with disabling the radio at sea with a possible fine of $10,000.

Joe stayed out of college until the fall of 1912 in order to earn money. While on the ‘J.B. Stetson’ he heard his first SOS. A ship had lost its propeller and was asking for aid. The ‘Stetson’ poured on every ounce of steam, arriving at the scene only to find the stricken vessel already in tow. During this period, Joe and his pal Watson spent some time on the “beach” in S.F. “living largely on free lunch at Casserly’s Bar,” so that when he finally shipped out for Honolulu on the ‘Santa Rita’ Joe had just 30 cents in his pocket. Coming into HA he asked the skipper for $10 advance so he could get tattoos but was promptly talked out of it. Following this trip the ship sailed to Panama where Joe witnessed the celebration of completion of excavation for the canal.

The summer of 1912 found Joe with his first land station assignment at United Wireless Station ‘PC’ at Astoria. As junior operator he was given the graveyard shift, and recalls it “turned out to be my most interesting job by far.” “My trick handled all the real long-haul traffic and there was plenty of it, with the Jap passenger vessels bringing immigrant labor over. Most of them were bound for the sugar-beet country of Idaho. All the traffic was in the Japanese language; but the intriguing part was that, after copying it all in Continental I had to turn ’round and put it right out on the Postal Telegraph loop to Portland in Morse, of course.” Joe relates that as a rule he would first contact the ships at from 1000 to 1500 miles out, but that their signals were so weak he had to use a non-scratching pencil with glass under the paper to further eliminate scratch sound, and then “hold the ‘phone cord away from my clothes for maximum silence. Believe me, I earned that 80 bucks a month.”

In 1913 Joe and Cliff shipped out on the ‘Humboldt,’ a small passenger vessel plying the Inside Passage from Seattle to Skagway. This soon was a “drag” for the two young, restless beavers, since they were required to traffic as the ship passed through long stretches of “dead spots” which predominate in these landlocked waters. They did, however, have two exciting episodes–once, when Watson was chased by a drunken sailor armed with a belaying pin, and again on receipt of an SOS from the ‘Northwestern’ which had run aground on Point No Point and they arrived on the scene only to find that another ship had beaten them there. After a few months of this dull life, Joe and his friend sought more exciting assignments. After being unsuccessful in getting berths on the same ship, they separated. Joe finally shipped out on the ‘Admiral Schley’ on the Seattle–SF run. The wireless gear, made by Kilbourne and Clark, had a “phoney” circuit to get around patent restrictions; its 60 cycle quenched gap produced a note “like rough escaping steam.” Joe and his second op Jack Wiehr were kept busy copying Honolulu’s press each night with the aid of a “wonderful piece of carborundum that we kept in adjustment for months at a time.”

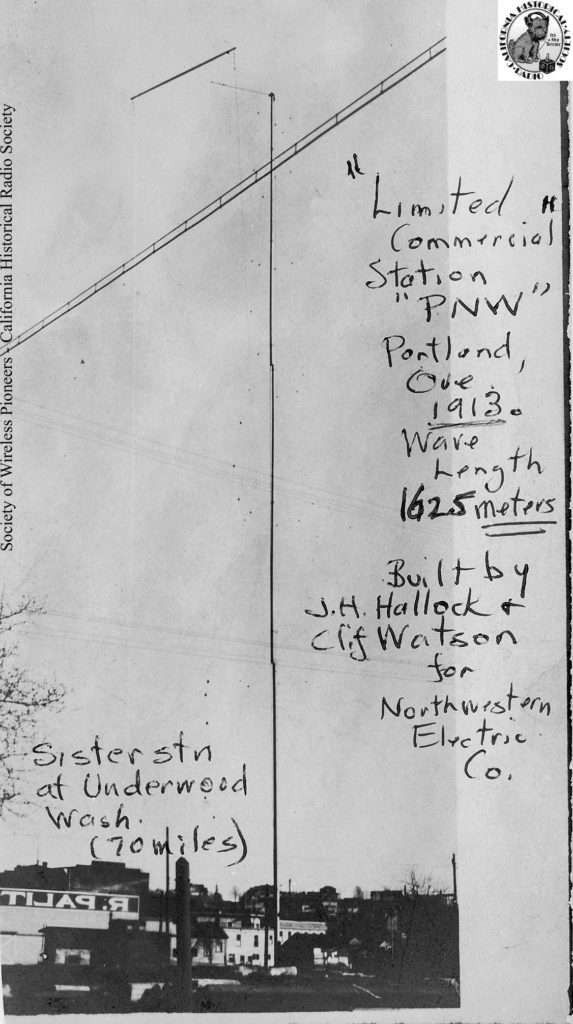

After several months of sea duty on the Seattle-Portland-SF run, months packed with incidents which would make stories in themselves, Joe headed for the “beach” and some shoreside life. He got a job as a cable splicer’s helper with the Northwestern Electric Co. It seems they were having trouble with their hiline telephone line, which was strung for 70 miles on the same poles as their 66 kV power line; it was plagued continually with noise, forest fires and silver thaws.[1] Joe persuaded the company to let him install two 2 kW former amateur stations, one of which was described earlier in this saga as his own. These two stations, one at either end of the line, operated on 1825 meters [164 kHz] with the calls ‘PNW’ and ‘UND,’ as limited commercial stations at Portland and Underwood, Washington, and performed well for four years, handling hundreds of company messages when the telephone line was down or unservicable. Joe worked at the hydro plant at Underwood as well as serving as chief operator of the “wireless.” His pal Watson joined him there; the two men were happy together at Underwood until 1915.

Joe’s restless nature soon got the better of him. He decided to ship out again, this time with the American Hawaiian Line’s SS ‘Nevadan’ bound for the east coast. It was Joe’s first experience with a quenched gap transmitter, and he thoroughly enjoyed it. During the trip across the Caribbean, the ship encountered a nasty blow out of the northeast. The wireless cabin was on the main deck and, with a fully loaded ship, not far above the sea. To keep the cabin from being flooded, heavy storm doors were put up, thus barricading Joe into the cabin. Solid green seas were hitting his storm door so hard the water squirted through every unseen crack; he soon had several inches of water under foot. The ship ran ashore in the night on a tiny island in the storm, but fortunately was undamaged and able after daylight to float free at high tide. The only casualty was the second mate, whose “ticket” was lifted for six months.

Joe returned to Portland, where he took examinations for Radio Electrician, Navy Yard, and Radio Inspector, Dept. of Commerce. In June 1916 he accepted a job with the Navy and reported to Mare Island. He soon was sent to San Diego as an assistant rigger on the antenna installation for the first high-power (200 kW) arc station there. In November he was offered a job with the Dept. of Commerce, and reported to Washington, D.C. as an assistant radio inspector at $1200 per year. After several months, Joe decided he preferred construction work. He resigned and returned to Mare Island, where in due time he was promoted to Shore Station Supervisor; he worked on numerous stations on the Pacific Coast and in Alaska.

During Joe’s sojourn in the Navy he played a major role in the construction of the world’s largest radio station (at the time) located at Bordeaux, France. Preliminary to crossing the Atlantic, he was assigned to ‘NSS’ Annapolis as an observer on the 500 kW Federal arc installation there, engaged in making antenna and counterpoise measurements. Arriving in France in the Fall of 1917, he settled in the little village of Croix d’Hins, the site chosen for the great Lafayette station. It was a huge project, employing a labor force of 600 German prisoners and 400 Spanish laborers in addition to the large U.S. Naval work party. Joe was an assistant engineer on the project. He describes the station; “The antenna was supported by eight 820-foot towers, was 400 meters wide and 1400 meters long, and had a capacity of 0.05 mfd. Yep, that’s right – 0.05! With the 1000 kW arc the radiation was well over 600 amperes at frequencies in the neighborhood of 20,000 meters (15 kc). The arcs weighed 83 tons each, and the helix was 15 feet in diameter, and the same in height, wound with 2 1/2 inch ‘Litz’ on porcelain legs. 79 keys in series were used to break the one loose-coupled turn, which made ‘compensating’ keying. The station was sold to the French at our cost after the war. This was the highlight of my radio career, and I was proud to be part of that huge undertaking.”

Another undertaking, dangerous in its execution was participated in by Joe during this period. In 1913 the Germans had built the second highest tower in the world at their Tuckerton New Jersey station. This tower, 855 feet in height, had rocker plates, supported by 18 solid glass cylinders 10″ in diameter, situated at its base, as well as at a point 550 feet up. When the Navy took over the station in 1917, these glass insulating cylinders were crumbling, and it was decided to replace them with steel, making it a grounded tower. Joe tells how he and his friend Joe Ryall, an expert rigger, performed this “little chore.” “For many days we climbed the tower morning and noon, and, with a battery of hydraulic jacks and much timber “shoring,” lifted the upper 300 feet and replaced all the insulators under the rocker plate. Next, we rigged a large barrel in which we would be pulled, one at a time, up to each of the 24 huge guy insulator assemblies, which were 7 feet long and weighed 1600 lbs! There, with the aid of a six-foot open-end wrench, the two of us would compress each unit ’til we could pull out the four glass cylinders and replace with steel! This took weeks of the hardest labor, at heights up to 750 feet and nothing below us but empty air!

“Then came the crowning achievement. With hydraulic jacks with a total capacity of only 550 tons, we had to lift the entire tower (480 tons) to a height of 3/4” in order to replace the glass insulators. In doing so we were of course lifting also the 72 guys by that amount! It was impossible to get any more jacks, so, after installing all our timber shoring, we set to work with a crew of ‘gobs’ on the jacks. As the tower slowly lifted, the overladen jacks started to leak alky.[2] But we had to keep going, and there ensued certainly the worst hours of our lives, as we painfully and ever-so-slowly raised the tower, clawing out each crumbling glass and sliding the steel in its place. At times we felt the worst would happen, the jacks collapse, and the whole tower slide off its base, with Lord knows what result. But with all of us driven by fear to work as we have never since, we made it! A passing vote of thanks to those husky seamen who pumped as tho’ they had a sinking ship under them. Perhaps the old tower has long since gone to its great reward, but at least on that day we all did our best to ensure that it could and did handle a whole lot of Navy war traffic from that time on.”

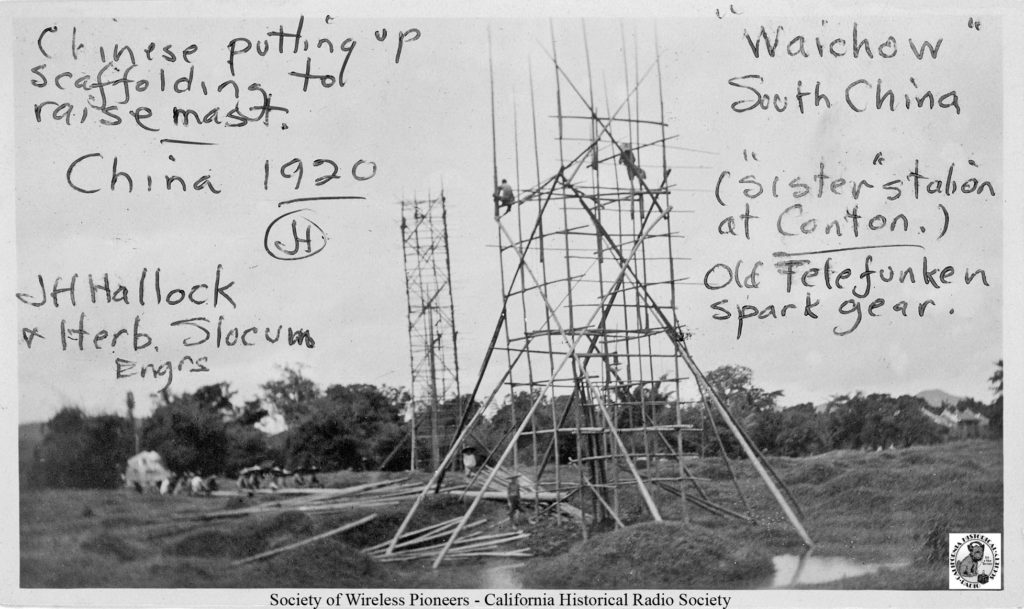

Joe was back in “civies” in the fall of 1919, headquartered at Mare Island. He left the Navy Yard in 1920 to accept a very remunerative contract to go to South China to install a group of DeForest Radiotelephone stations for the South China Development Co. Arriving with his wife at Canton, they were billeted in a big storehouse on Shameen [Shamian] Island, the International Settlement in Canton. The party of six engineers, of which Joe was one, soon became involved in the revolution of Sun Yat Sen, whose forces seized their ship with all their radio gear aboard. Joe and his partner were given some old Telefunken spark gear and told to install land stations at Canton and Waichow for all Army communications. For several weeks they handled thousands of words of army traffic on 1000 meters. Eventually, “their side” was defeated, the Waichow station was lost and the army fell back on Canton. Before long Canton itself was captured by the revolutionists. Shameen itself had no casualties and no foreigners were molested.

The young American-educated Chinese, Tomm Gunn, who had brought Joe’s party of engineers to China got them all together at his own peril, and provided them with tickets back to San Francisco, as well as full salary up to the date of arrival there. After doing this, Tomm and two generals escaped to the North and were never heard from again. Joe was approached aboard ship by one of Sun Yat Sen’s staff who subtly conveyed that “all of them were fortunate to have gotten away without a few hatchet marks or bullets here and there!”

Back home in December 1920, Joe went to work for Mackay Radio and was sent to Los Angeles to lease the land and build a marine and point-to-point station at Clearwater, California (‘KOK’). Here he erected a pair of 300-foot masts and a nice building in which he installed 60- and 30-kW arcs and a 5-kW marine spark transmitter. Control was in L.A. Meanwhile, Joe and his old buddy Cliff Watson had been mulling over returning to Portland, starting a radio store and cashing in on the rapidly mushrooming broadcast business.

They reached a decision in December 1921, resigned from their jobs and opened their business “Hallock & Watson Radio Service” in Portland. They secured the first broadcast license issued in Portland and built a five-watt broadcast transmitter (‘KGG’), getting on the air in February or March 1922.

They operated KGG (later 50 watts) until the end of 1924, when their business had grown to such an extent that they could not afford to give away so much time on free broadcasting (no one had thought of selling time up to then). So they merely turned in their license and closed the station. They turned their efforts to building battery broadcast receivers under the copyrighted name of ‘Halowat’; they built some 4000 sets. They also got into the broadcast transmitter business building stations KFEC, KFJR, KOIN, KBPS and numerous others in the Northwest. Following the crash of 1929 the company was just “hanging on the ropes” and down to one employee by 1932, when they won a $14,500 contract to build and install the Portland Police radio system. This enabled them to get out of debt and liquidate the company in 1933. The summer of 1933 found Joe back with Mackay Radio. He was given the job of building a new receiving/control station at Manhattan Beach for the Los Angeles area, replacing the old one at Hermosa Street.

Halowat TR-5 Receiver. Collection of CHRS, Courtesy of Bart Lee.

In the fall of 1933 Joe found himself “pretty low down the financial ladder.” He got a job announcing at station KGW/KEX at $30 a week. He soon decided, however, that he would never get rich that way, so in 1935 he wrote the FCC advising them that he had been a radio inspector in 1916/17 with the Commerce Dept. and asking if he might be reinstated. In due time, he was accepted by the FCC. During the next 25 years Joe was very happy, serving at Portland, Galveston, Washington D.C., San Francisco, Seattle, and for seven years before his retirement in 1960, in charge of the Portland office.

It is with deep regret we must report the death of Joe Hallock in June 1972. Truly, Joe was one of our colorful members. (EHB: 3-3-73)