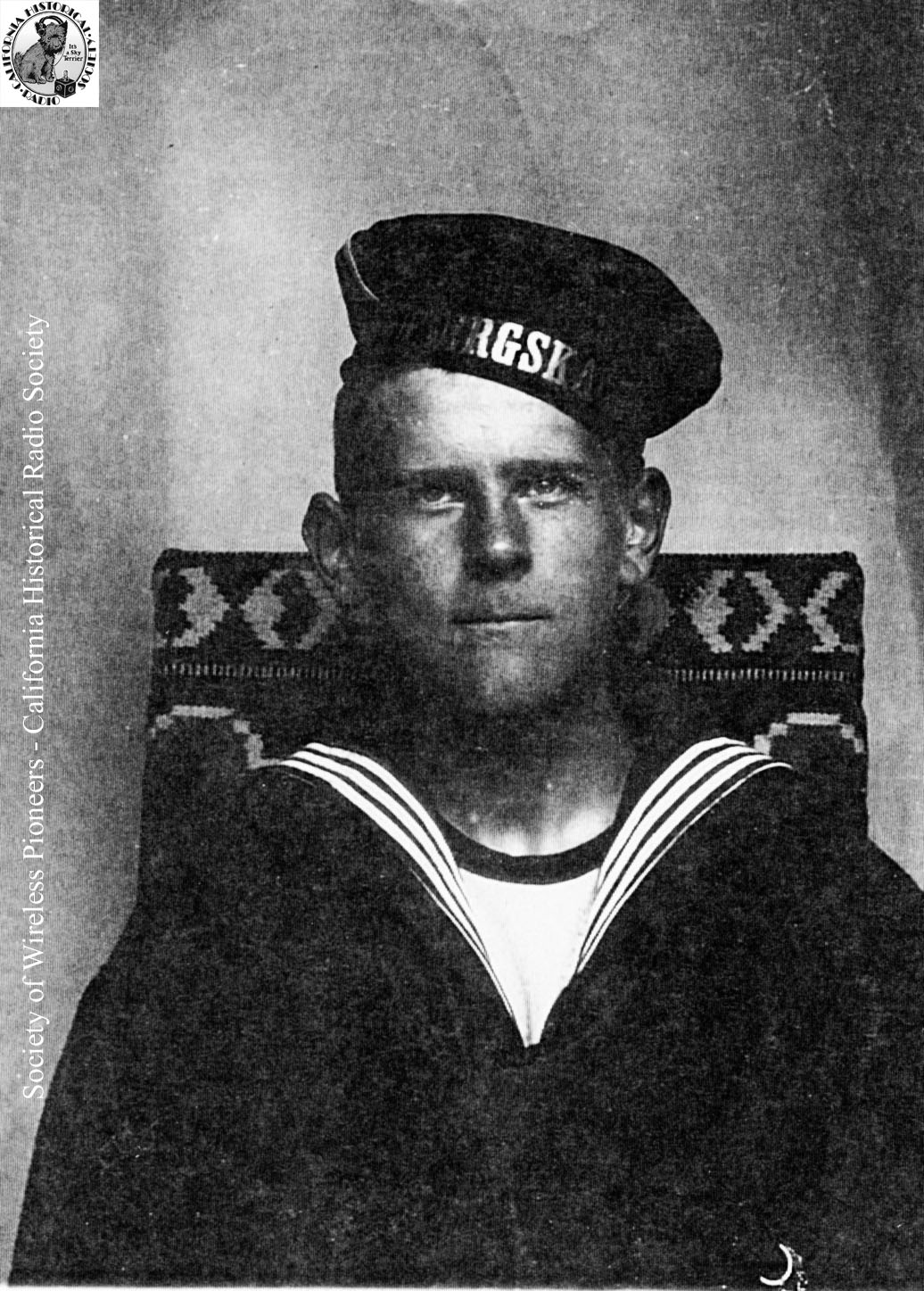

Pioneer Portraits: Charlie Lindh, 676-SGP

Most old-time ship wireless operators started out in wireless (or, in a few cases, as land-line telegraphers) and then went to sea. Not so for Charlie Lindh, a sailor first who then went on to become “Sparks”. Born Karl Agne Ragnwald Lindh on May 6, 1887 in Vesterwik, a coastal town in southern Sweden, a Naval career had been decided for him by his family. He “learned the ropes”—quite literally— in the Swedish Navy on a windjammer.

This career path, however, did not agree with Charlie, who left the Navy to become an ordinary seaman on another sailing ship, most likely the Princess Wilhelmina. Its captain later noted that Charlie was sober (always an important quality for a sailor) and dependable.

Eager to learn English, he then decided to sail under the British flag, signing on to the ship as Charles Agne. This gave rise to some consternation in his family, especially when they learned the ship was bound for that Babylon-by-the-Bay, San Francisco. “They were sure they would never see him again,” his son Carl wrote many years later.

Charlie might have been inclined to agree with them after some time on that vessel. The ship was not a happy one. When some delegated sailors went to complain to the Captain about the food, which consisted mostly of buggy bread, they were informed that the bugs were the only fresh meat they were going to get on that trip.

After rounding Cape Horn (the Panama Canal not yet existing), the ship duly arrived in San Francisco not long after the 1906 earthquake, then sailed North. On shore leave in Tacoma, Charlie was spotted by a friend of his brother’s, who introduced him to Miss Zella Maud Turner, who would one day become his wife.

In Tacoma he signed on to a ship of the American Hawaiian Steam Ship Line, which may have been the SS Mexican. After a number of trips between the mainland and Hawaii, Charlie signed off the ship as quartermaster and stayed in Hawaii. There he found work on a ranch on Molokai, the island known for its leper colony. On Molokai he saw a newspaper ad from a Hawaiian school that taught wireless. He was intrigued. Soon a “sparks” as well as a U.S. citizen, Charlie got a job at commercial station KHK.

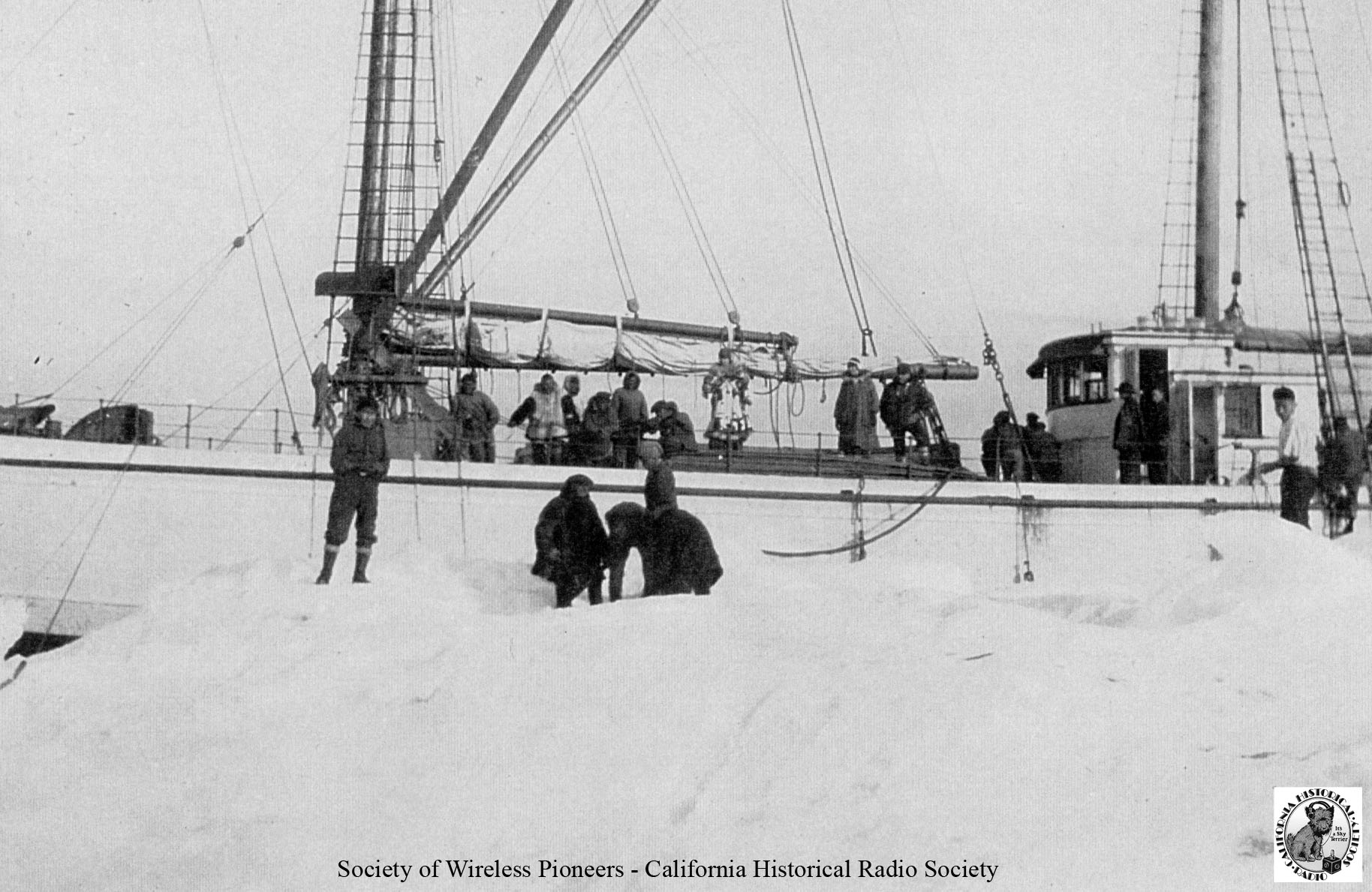

After a time, Charlie decided to move back to the mainland, sailing back to San Francisco. Some friends who met him there noticed that he didn’t look well. Charlie attributed this to Hawaii not having the “proper seasons” he needed as a Swede. He signed on to a ship going to Alaska.

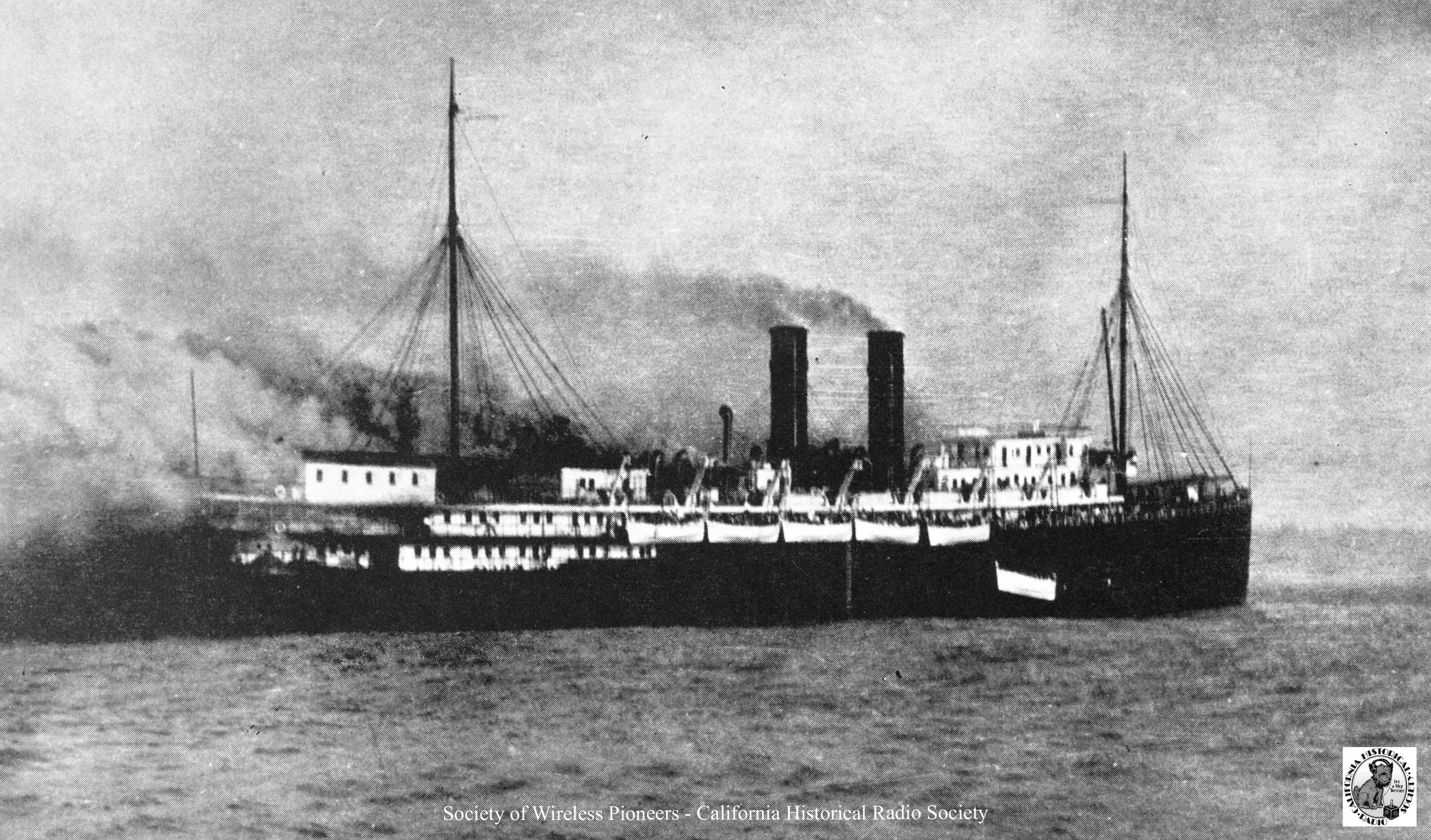

Sure enough, by the time he returned he was in full health. He spent the years prior to World War I as a ship radioman. He must have been quite skilled; among the ships he served on was the pride of the Pacific Coast Steamship Company fleet, the passenger liner SS Congress. Charlie was Second Operator, the First being legendary West Coast wireless pioneer (and honorary SoWP member) Henry Dickow.

On September 14, 1916 while bound for Seattle the ship caught fire off Coos Bay, Oregon. According to the book “Ships That Sail No More,” by Giles T. Brown (University of Kentucky Press, 1966) the passengers were not informed of the fire until attempts to smother it with steam had failed. By the time the order to abandon ship was given, dense smoke and intense heat made it impossible to use the lifeboats on the leeward side. You can see this in the photo above, reproduced from “Pacific Coastal Liners” by Gordon Newell & Joe Williamson (Bonanza Books, NY, 1959).

Despite the smoke, thanks to the SOS sent by Charlie Lindh (or Henry Dickow; the Sparks Journal gives two different accounts), all 428 passengers and crew members escaped a fiery death. Strangely, though a smoldering wreck gutted by fire, the Congress still stayed afloat. She was eventually rebuilt and served for many more years.

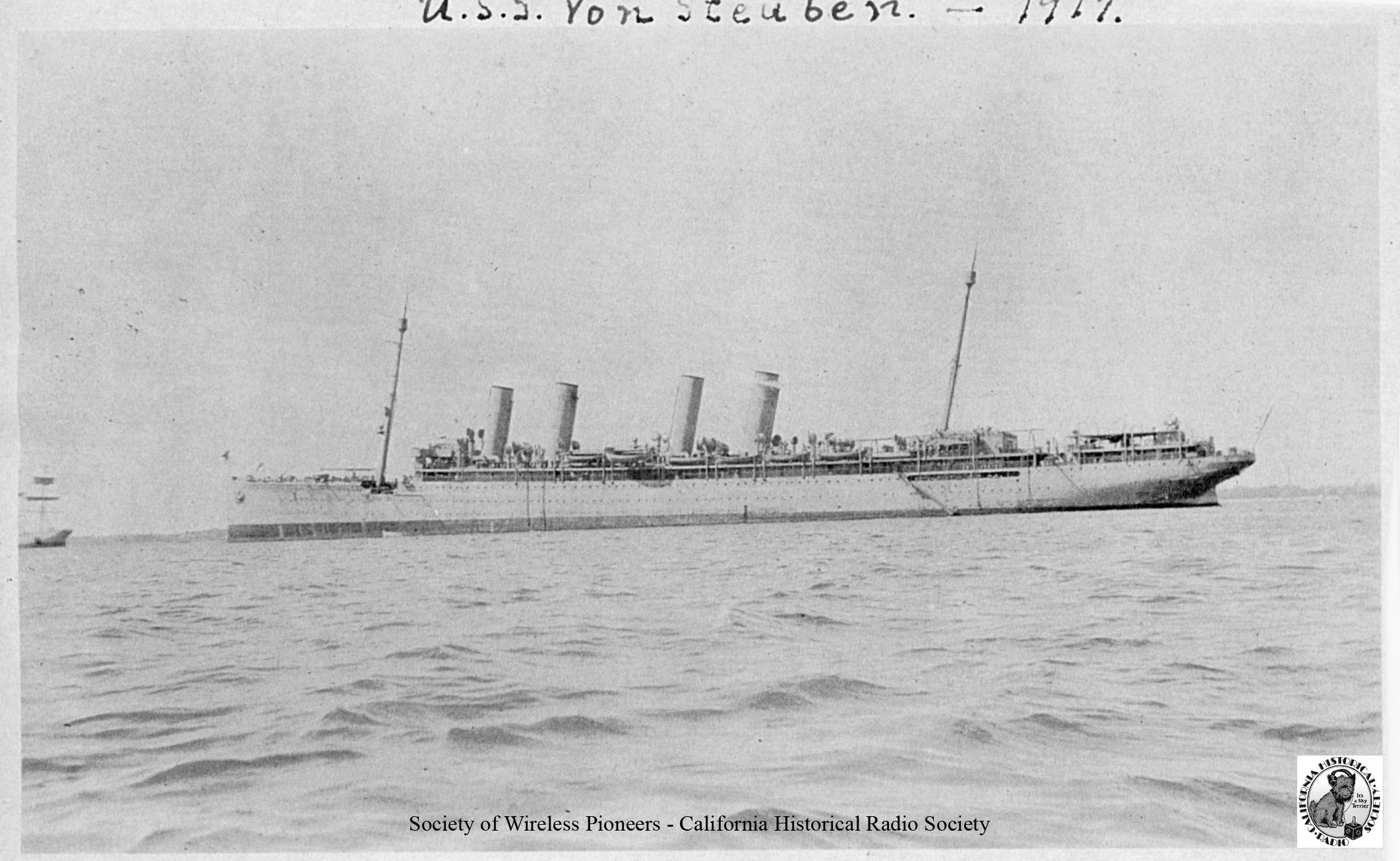

As did Charlie Lindh, who enlisted in the US Navy in 1917. He served as Chief Petty Officer in charge of radio on the USS Von Steuben, a troopship ferrying doughboys from the East Coast across the dangerous Atlantic “over there” to France.